Jun 9, 2020|

China’s Stimulus Sceptics Need Not Fear Side-Effects This Time

This article was first published on FT.

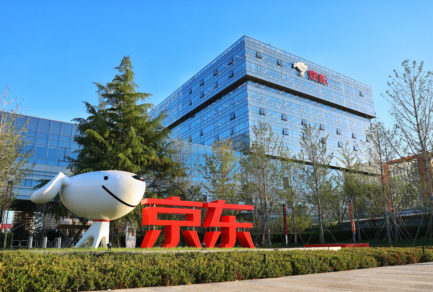

by Jianguang Shen, Vice President of JD.com and Chief Economist of JD Digits

At last month’s National People’s Congress, China unveiled a much-anticipated fiscal stimulus package to counter the damage caused by the Covid-19 crisis to the world’s second-biggest economy.

The virus-fighting spend, which amounts to an extra Rmb3.6tn ($500bn), or around 4 per cent of China’s annual economic output, will be paid for by the issue of special Treasury bonds for pandemic relief, as well as infrastructure-bound local government special bonds and a wider fiscal deficit.

For many in China, the intervention is reminiscent of the Rmb4tn stimulus introduced by Beijing after the 2008 financial crisis. Held up as a painful lesson on the risks of ultra-loose fiscal policy, it has since dominated economic debate. But where does this stimulus phobia come from?

Aimed at boosting sagging demand, the financial crisis-era programme involved massive public infrastructure investment, social welfare spending and rural development. True, it left China with a painful legacy that was felt many years later, such as bloated local government debt, a red-hot housing market and hordes of zombie companies. People understandably fear a new debt-fuelled bubble from the latest spending spree.

However, the 2008 stimulus package also proved to be a strong and timely relief from the maladies of the period. The side-effects would have been held in check if the structural flaws in China’s economy had been better addressed.

When the world was reeling from the aftermath of the financial crisis, China’s policymakers were absolutely right to worry about the downturn it would cause. Months later, the country’s exports would drop, unemployment rose and many small businesses collapsed. Stimulus enabled China to quickly restore its economic vigour and the country went on to overtake many of its rivals in the ensuing decade.

The public expenditure did not just prop up aggregate demand; in particular, huge spending on infrastructure has paid off. A high-speed railway network, new airports and logistics — mostly built after the crisis and once deemed as being premature investments — have shaped the country’s urban clusters and made its manufacturing sector more competitive. China’s share of the global manufacturing sector’s value-added rose from 14.4 per cent in 2008 to 28.2 per cent in 2018, according to our analysis of World Bank data.

China now finds itself in a completely different landscape. The current situation calls for even greater urgency than 2008. As the battle against Covid-19 dragged on, China’s GDP shrank 6.8 per cent in the first quarter of 2020, the steepest year-on-year fall ever recorded. By contrast, the country’s economic trough between 2008 and 2010 was a 6.4 per cent year-on-year expansion.

Although April’s data contained some green shoots, domestic demand lagged behind supply. While the added value of industrial production grew 3.9 per cent, retail sales and investment contracted. And as the world braces itself for a sharp technical recession, with the US economy heading for a 38 per cent annualised decline in inflation-adjusted output in the second quarter, a temporary rebound in China’s exports in April disguised the grim reality that more and more foreign orders were being cancelled.

Beijing has vowed to work on what it calls its “six priorities”: employment, basic livelihood, companies, food and energy security, stable supply chains and smooth operation of government. For example, saving jobs and small and medium-sized businesses would call for something similar to the US’s Paycheck Protection Program. A more resilient supply chain suggests increased infrastructure spending.

China has more room for manoeuvre than other big economies. According to IMF’s fiscal tracker, China’s Covid-19 support packages (including spending, loans and guarantees) amounted to only 2.5 per cent of its gross domestic product by April, compared to 34 per cent for Germany, 20.5 per cent for Japan and 11.1 per cent for the US. Even after adding the measures announced at the NPC, China’s fiscal commitment is still a far cry from that of western economies.

The country also boasts a fresh and promising pool of projects. Of course, much of the fiscal spending will be earmarked for the six priorities, but the spotlight should also be turned on those “new infrastructure” investments such as data centres, industrial facilities powered by artificial intelligence and cold-chain logistics for products such as frozen goods, all of which could unleash China’s potential as an economic powerhouse over the next decade.

A healthy dose of fiscal action serves both shorter-term stability and longer-term prosperity. Of course, stimulus alone is no panacea. The best way to overcome the sceptics is to build on a well-structured and carefully targeted spending plan. Further efforts to rejuvenate the post-pandemic economy — through measures such as rural land reform and a further opening-up of the financial sector — remain key to China’s sustained growth in an increasingly uncertain world.

JD Logistics Upgrades Lower-tier Markets Program This Year

JD Logistics Upgrades Lower-tier Markets Program This Year